spermatogenic Musings

the mating of the shrew

January 30, 2025

An adult male Southern Short-tailed Shrew (Blarina carolinensis) met its untimely demise in early January in our ice-cold pool. As a reproductive biologist, I was interested to learn about these fascinating critters — they are evidently fairly ill-tempered nocturnal mammals with extraordinarily high metabolic rates supported by an enormous appetite for insects, crustaceans, amphibians, reptiles, and even small mammals. They incapacitate their prey with venomous saliva, and even store live animals such as snails in their burrows to feed on over the winter. As is the case for most mammals living in temperate zones, they have breeding seasons. During the breeding season, their testes have full spermatogenesis; in the ‘off-season’ they are infertile and their testes undergo recrudescence, with the seminiferous epithelium containing only Sertoli cells, spermatogonia, and perhaps a few primary spermatocytes. Since here in North Carolina the breeding seasons are reported to be from March-June and September-November, it was surprising that this far in advance this male had full spermatogenesis (left) and a cauda epididymis full of sperm (right). Little is currently known about the molecular and cellular mechanisms that direct spermatogenesis changes in seasonal breeding mammals like this shrew that prepare them for fertility, but this may be a future project in the lab.

how are germ cells & tractors alike?

April 2, 2021

I’m still working on the punchline…

Actually, this was something I was thinking about today while mowing our front fields. I mow them twice a year, and it provides a great deal of satisfaction. It’s so different from research - in the lab, it takes a long time to plan and do the experiments, interpret the results, write, submit, and revise grant proposals and manuscripts… but when I cut grass, the results are instantaneous!

Today, I was thinking about science, as I often do while I’m on my tractor. I was thinking about how almost nothing is known about the subjects we’re currently studying in the lab - spermatogonial differentiation and meiotic initiation in mammals. The things we do know come largely from knockout mouse studies - we delete a gene, either in germ cells or in the entire body, and then determine the consequences. I realized I also know very little about how my tractor works - I add diesel fuel and check the oil and hydraulic fluids, and of course I know how to operate it, but that’s about it. I was thinking about how the “knockout approach” could be used to learn more about my tractor - I could take a hammer, a wrench, and/or a screwdriver and remove or break something and then see what happens. Will the tractor start? Will it move, in forward and reverse? Can I raise and lower the loader? Will the PTO run? If the answer was ‘no’, then would conclude the part I destroyed was “required” for that function. It wouldn’t necessarily be instructive in terms of how that particular system worked, unfortunately. But, what if I removed a part that wasn’t required for the normal functioning of the tractor? For example, we live in Greenville, and there are no hills here - the land is as flat as a pancake! So, if I cut the cable for the emergency brake, I’d probably never figure out its function because my tractor wouldn’t roll down a hill when it wasn’t in gear. I’d conclude (incorrectly) that that part was non-essential, but I would be wrong because I just didn’t know how to assess its function correctly. There are also plenty of parts on the tractor that may be “non-essential” - cosmetic, or enhance rider comfort, or function to prevent long-term wear and tear... By removing them, it would be really difficult to determine their function.

I do think there are some important parallels to science - in the end, this hypothetical approach of dismantling my lovely tractor part-by-part would not an efficient way to figure out how it works. Yet, this is the most common approach we’re currently using as a field to define the mechanisms that underlie germ cell development. I worry that, using these tools, it will be centuries before we figure out how germ cells work!

When does mammalian meiotic initiation occur?

September 12, 2019

Some ongoing experiments in the laboratory have caused us to think a good bit about meiosis. More specifically, the initiation of meiosis.

I first wanted to answer the question for myself: “at what point do mammalian germ cells initiate (begin) meiosis I?”. So, I went to textbooks and review articles, and then to the primary literature, and came away… well, a bit surprised. It seems there isn’t a clear consensus answer to this question.

So, what things are known? Well, we know that premeiotic germ cells (oogonia in the ovary, spermatogonia in the testis) divide by mitosis to amplify their numbers before entering meiosis. These oogonia and spermatogonia complete their last mitotic division and become preleptotene oocytes (in the fetal ovary) and preleptotene spermatocytes (first appear in the postnatal testis at ~P8, and then at each stage VII of the seminiferous epithelial cycle during steady-state spermatogenesis). We also know oogonia and spermatogonia have unique morphological characteristics - in the testis, in comparison to their predecessors (type B spermatogonia), preleptotene spermatocytes are smaller cells, with round nuclei, reduced cytoplasm, and (in fixatives such as Bouin’s) a characteristic chromatin condensation pattern. We know preleptotene spermatocytes and oocytes then replicate their DNA, which takes them from 2N/2C to 2N/4C; but, instead of dividing, they retain this doubled genome and enter a protracted prophase of Meiosis I.

So, when do mammalian germ cells specifically initiate meiosis? The possibilities, as best as I can tell, include:

With the transition of oogonia/spermatogonia to preleptotene oocytes/spermatocytes (after all, the convention taught to medical and graduate students is germ cells with the suffix ‘gonia = mitotic, ‘cyte = meioitic, and ‘tid = postmeioitc). The distinct appearance of preleptotene oocytes/spermatocytes implies they are undergoing significant molecular and cellular changes.

In preleptotene oocytes/spermatocytes just before the unique DNA replication-not-followed-by-division. If there is a molecular signal that prepares them for this decision, then it would be expressed prior to this stage and be predicted to be required for this step.

In preleptotene oocytes/spermatocytes just after the unique DNA replication-not-followed-by-division? At this point, they are truly unique, and have clearly diverged from their spermatogonial predecessors, as they have decided not to divide, but retain twice as much DNA as a normal cell and enter the prolonged prophase of meiosis I. If this is the case, then there should be some molecular signal(s) preventing division.

The more things change, the more they stay the same…

August 1, 2019

“Spermatogenesis, like other basic biological problems, has been investigated in a rambling fashion depending on the personalities of the scientists involved, on the methods accessible to them, and particularly on the animals they happened to use as objects for study. At any given time in history, the sum total of activity in the field has produced a climate of opinion which characterized and determined the individual investigations and the concepts which developed from them. Our present epoch is no different in this respect…”

Edward C. Roosen-Runge in The Process of Spermatogenesis in Animals (1977)

How does spermatogenesis work in seasonal-breeding mammals?

August 20, 2018

Most mammals exhibit seasonal breeding behavior. Breeding seasons vary by species and by latitude, but are precisely coordinated with the length of the gestation period so that offspring are born in the most favorable time of the year for their survival. During the breeding season, changes in photoperiod and/or food availability are correlated with activation of the hypothalamic axis and increased serum testosterone levels as well as cyclical growth of the seminiferous epithelium and appearance of the full complement of spermatogenic cells and the production of spermatozoa. Outside of this breeding season, sexual behavior is reduced or absent, testes are small(er), and the seminiferous epithelium regresses to contain Sertoli cells plus spermatogonia and or spermatocytes and perhaps spermatids.

The seasonal growth and regression of the seminiferous epithelium has been characterized at the histological level in multiple species (e.g. grizzly bear, mole, whitetail deer, armadillo, and even some marine mammals); however, the molecular mechanisms underlying these changes are unknown. It seems reasonable to suspect that the well-documented seasonal changes in testosterone levels coordinate and regulate the epithelial changes described above. However, in mice the loss of testosterone signaling (Sertoli cell androgen receptor KO, or SCARKO), causes a meiotic block, which is not mimicked in all of the seasonal breeders, especially those with an earlier block in spermatogenesis, at the spermatogonia stage. It would be a great contribution for a laboratory to closely study spermatogenesis in a seasonal-breeding mammal model using modern technologies (e.g RNA-seq, proteomics, use of signaling inhibitors, hormone manipulation, etc.) to gain a more complete understanding of seasonal breeding regulation in mammals, and insights gained would surely be applicable to non-seasonal breeders such as humans.

Is the ‘first wave of spermatogenesis’ a rodent-specific phenomenon?

August 15, 2018

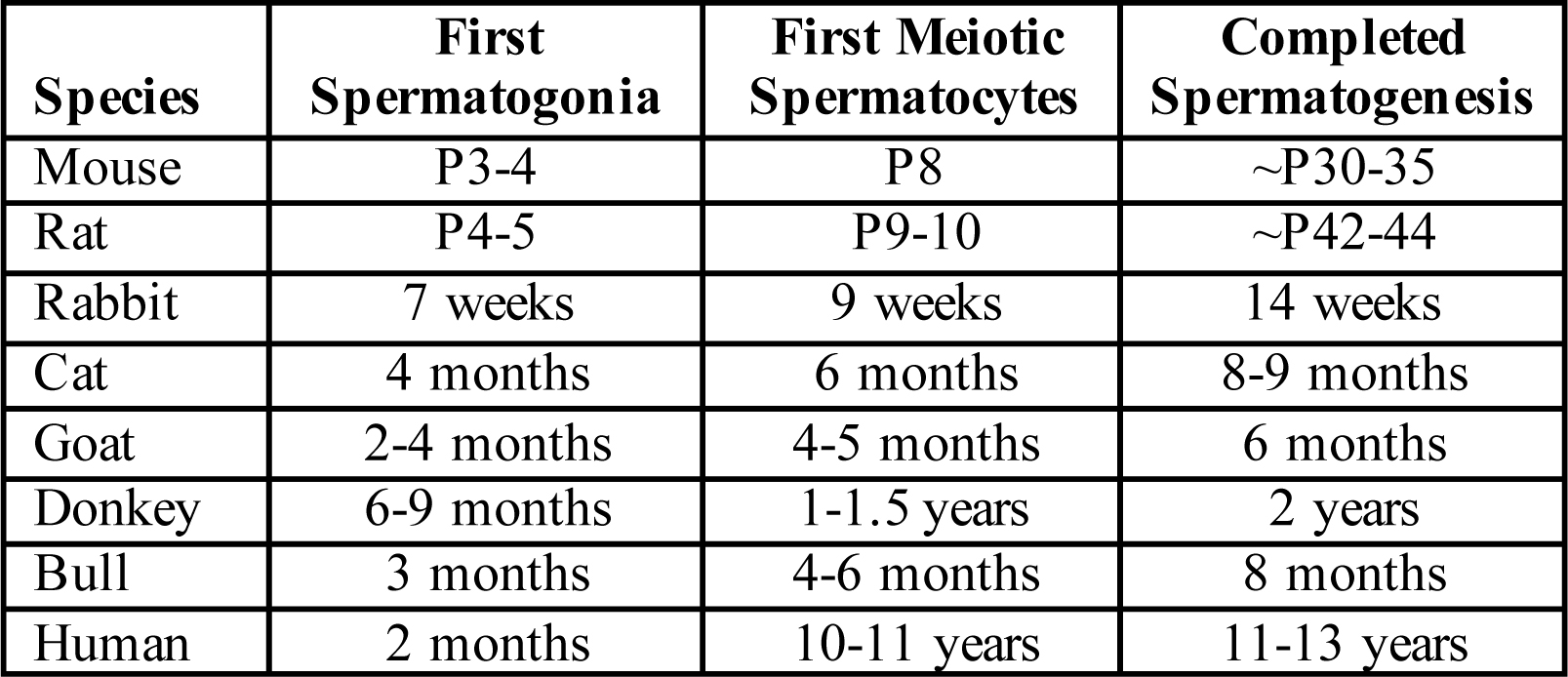

Timing of spermatogenesis in non-seasonal breeding mammals

From Geyer CB (2017) Setting the stage: the first round of spermatogenesis. Oatley JM, Griswold MD (Eds.), The Biology of Mammalian Spermatogonia, NY, NY: Springer Nature, pp. 39-63.

The short answer to this question is no, of course not!

At least one first round or wave of spermatogenesis occurs in all mammals. After the completion of the first wave, the testis is filled with the full complement of germ cells (spermatogonia, spermatocytes, spermatids, and spermatozoa), and progression of spermatogenesis is controlled so that production of the first sperm is temporally coordinated with the onset of sexual maturity (~7 weeks of age in mice, 12-13 years in humans). Multiple studies over the past 50-60 years have revealed that what does differ considerably between mammalian species is the timing of initiation of spermatogenesis and the interval following initiation until formation of the first testicular sperm (see summary table, above), which represent the finished product of the first and all subsequent rounds of spermatogenesis.

In seasonal-breeding mammals, a new first wave occurs at the beginning of each breeding season. It is unknown whether this first wave is initiated solely from spermatogonia, or from the latent spermatocytes or spermatids left over from the last breeding season in some species. In non-seasonal breeding mammals, the first wave often proceeds following the formation of type A spermatogonia in an uninterrupted fashion. This is particularly true in rodents, which have no temporal breaks in the first wave of spermatogenesis. This is in sharp contrast with humans, which have long temporal breaks between initiation and completion of the first wave. Human type A spermatogonia (termed Apale and Adark, respectively) form in the infant testis, but then become developmentally arrested (except for a small population of type B spermatogonia that often form around 5-6 years of age) until sexual maturity occurs with the onset of puberty at 12-13 years of age. At puberty, these type A and B spermatogonia presumably continue to develop in an uninterrupted fashion in response to the regulatory endocrine signals such as testosterone (T) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH).

I argue that studying the first wave of spermatogenesis (which occurs in all mammals) using rodents as a model will uncover the key regulatory molecules and pathways that underlie male mammalian germ cell development in all species, including humans.

What is the 'first wave of spermatogenesis'?

August 6, 2018

From Geyer CB (2017) Setting the stage: the first round of spermatogenesis. In Oatley JM and Griswold MD (Eds.), The Biology of Mammalian Spermatogonia, New York, NY: Springer Nature, pp. 39-63.

The postnatal process of mammalian male gametogenesis that begins with the differentiation of the first subset of spermatogonia and culminates with the formation of the first spermatozoa is called the first wave of spermatogenesis. As depicted above (P=postnatal day) for mice, it is during this first wave that fundamental cell populations are formed, the seminiferous epithelium matures, and macromolecular structures such as the blood-testis barrier are built that are required for lifelong fertility.

In general, shorter-lived mammals such as rodents initiate and then complete the first wave of spermatogenesis sooner than longer-lived mammals. The life of a rodent outside of the laboratory is perilous and often rather short due to constant threats of predation from birds, snakes, fish, and other mammals; a shortened time to sperm production ensures that rodents are fertile earlier in their lifespan. This maximizes the chances for productive mating encounters that result in pregnancy, which ensures passage of a male rodent’s genes on to the next generation.

However, is this first wave unique to rodents? I don’t think so, and will make the case in the next post that, although it occurs at widely variable times during development, a first wave must occur in all male mammals.

assessing spermatogonial hierarchies

July 23, 2018

Don't believe the image above, it is meant to mislead you. But please keep reading!

The premeiotic and mitotically dividing cells of the postnatal testis (spermatogonia) contain an active stem cell population. These stem cells divide to both maintain their numbers (via self-renewal) as well as produce large numbers of committed progenitors. At the end of mitosis, most spermatogonia do not physically separate, but remain interconnected via intercellular bridges to form growing chains, or clones.

One of the long-held tenets of mammalian spermatogonial development, both in the developing and adult testis, is that singly isolated spermatogonia (As) as well as those in pairs (Apr) have the highest stem cell potential, and this decreases with clone growth (into Aal spermatogonia). This model inversely correlating "stemness" with clone length was first proposed in 1971 in independent reports from Claire Huckins and E.F. Oakberg. The misleading image depicting these configurations is shown above, with bridges traced in yellow.

This ~50-year old hierarchical model has been challenged recently; it has been posited that long clones can fragment into smaller ones. By fragmenting, committed progenitor spermatogonia can 'reverse course' by de-differentiating to regain stem cell potential. However, before we can measure fragmentation of a clone, we must first unequivocally prove that it was a clone. Fortunately, determining whether adjacent spermatogonia are connected in a clone is rather straightforward, and can be accomplished by staining for intercellular bridge components, one of which is the essential germ cell-expressed gene product TEX14. This staining will reveal, beyond an assumption, whether spermatogonia residing close to one another are present (or not) in a clonal configuration.

Why is the above image misleading? Because this PLZF-stained seminiferous tubule whole mount is from a Tex14 KO mouse (generated in Marty Matzuk's laboratory). These mice are infertile and completely lack intercellular bridges; therefore, all spermatogonia are singly-isolated (As) and the appearance of connectedness into clones is simply an illusion.